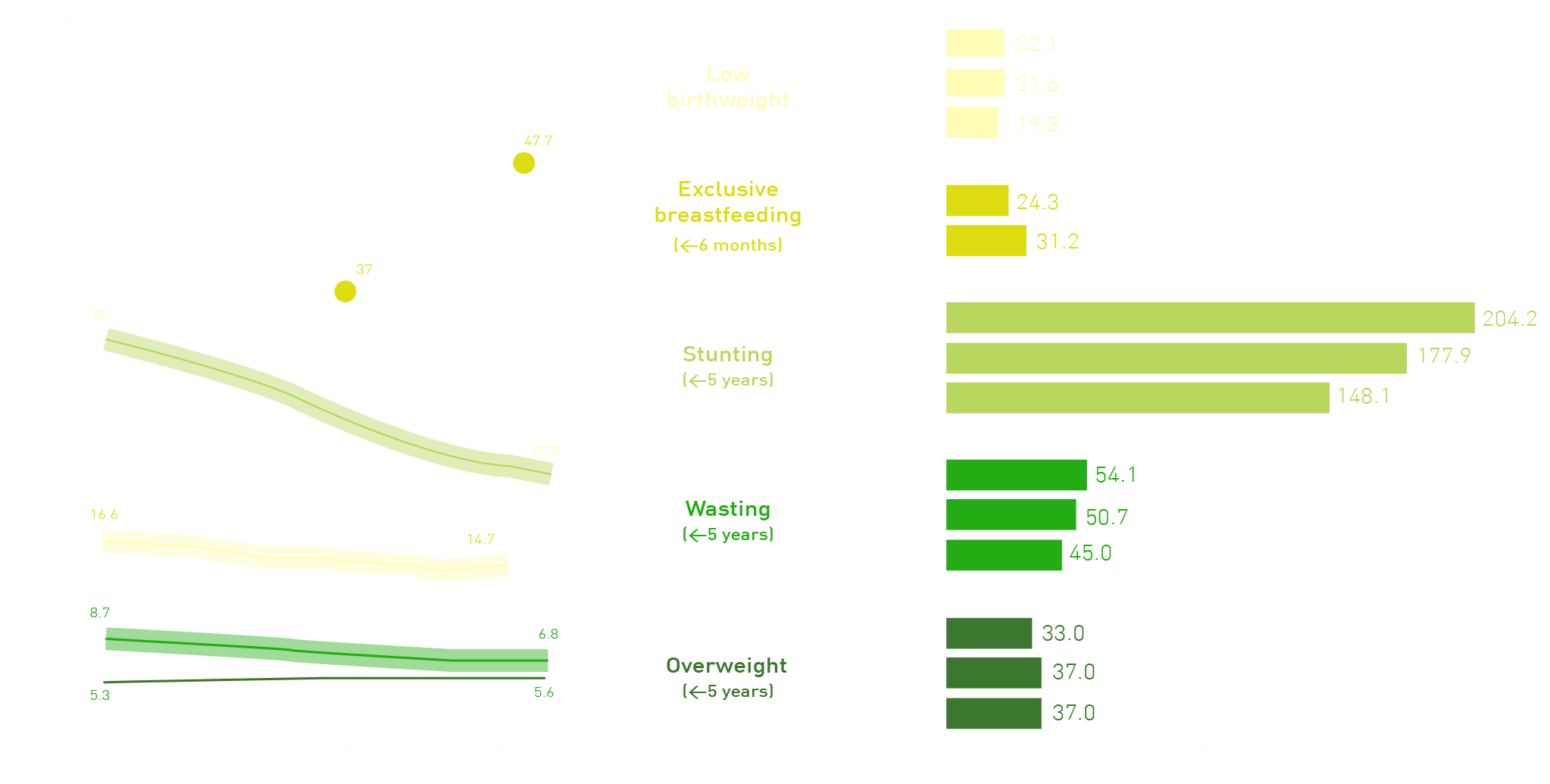

Traditionally, malnutrition was linked predominantly to shortages of nutritious foods in the face of poverty, conflict, and instability. Today’s landscape is more complicated. Rapidly growing and even wealthier economies also encounter malnutrition in the form of overnutrition.

This paradox arises as the most accessible and affordable foods are often calorie-dense yet nutrient-poor—high in sugars, salts, and unhealthy fats, rather than essential vitamins and minerals.

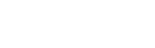

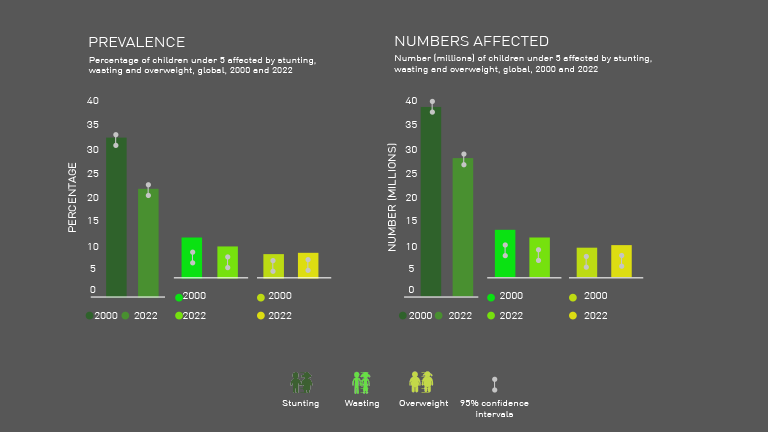

The 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report from the FAO concludes that “global progress toward nutrition targets remains off track,” highlighting the complex interplay of economic, environmental, and social factors.2

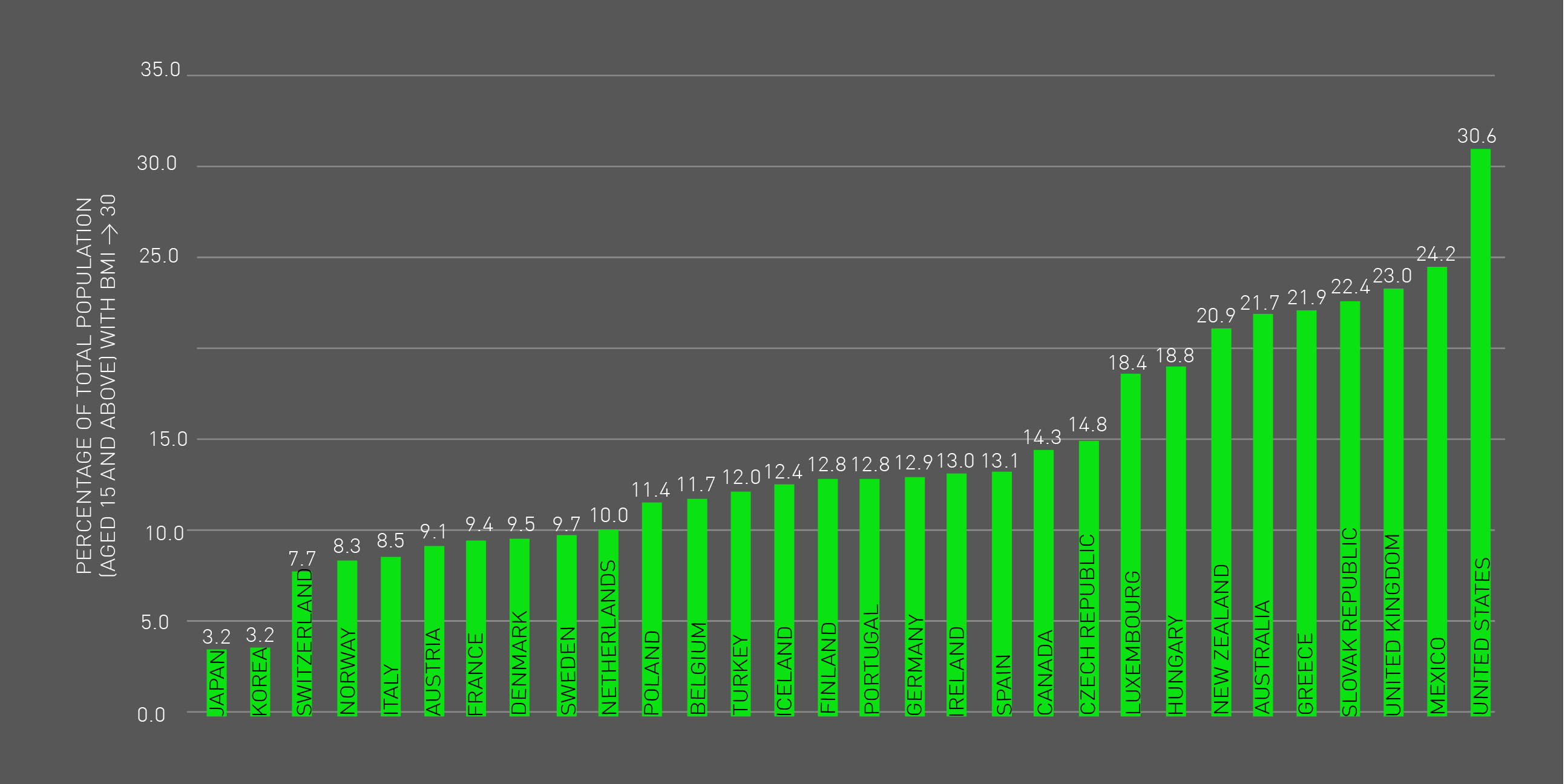

Economic pressures exacerbate the situation. Rising global food prices, stagnant wages, and government policies that subsidize staple crops for processed foods over nutrient-rich alternatives all funnel consumers toward less healthy diets.

A 2017 analysis found that U.S. adults consuming more foods derived from subsidized commodities faced a higher likelihood of obesity and metabolic risks.7 Inflation and supply chain disruptions further intensify these trends, affecting not only the world’s poorest regions but also wealthier nations contending with dietary imbalances.